Why Van Gogh Painted The Starry Night in an Asylum | iCanvas

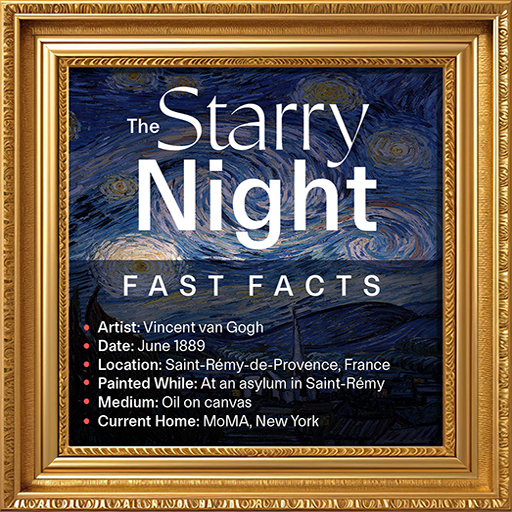

The Starry Night is one of the most famous paintings in the world, and one of the most misunderstood. Vincent van Gogh painted it in June 1889 while living at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France. But despite what many people assume, the painting isn’t a literal view from his window, and it wasn’t created in a single moment of chaos.

In this deep dive, we follow van Gogh’s own letters and the historical record to explain why he entered the asylum, what he could actually see from his room, and how he transformed confinement into one of art history’s most unforgettable night skies.

TL;DR: The myths are wrong: van Gogh didn’t just “paint what he saw” in a moment of madness. The Starry Night was a deliberate, composed masterpiece created during his asylum stay, shaped by real scenery, personal letters, and powerful artistic intention.

Table of Contents

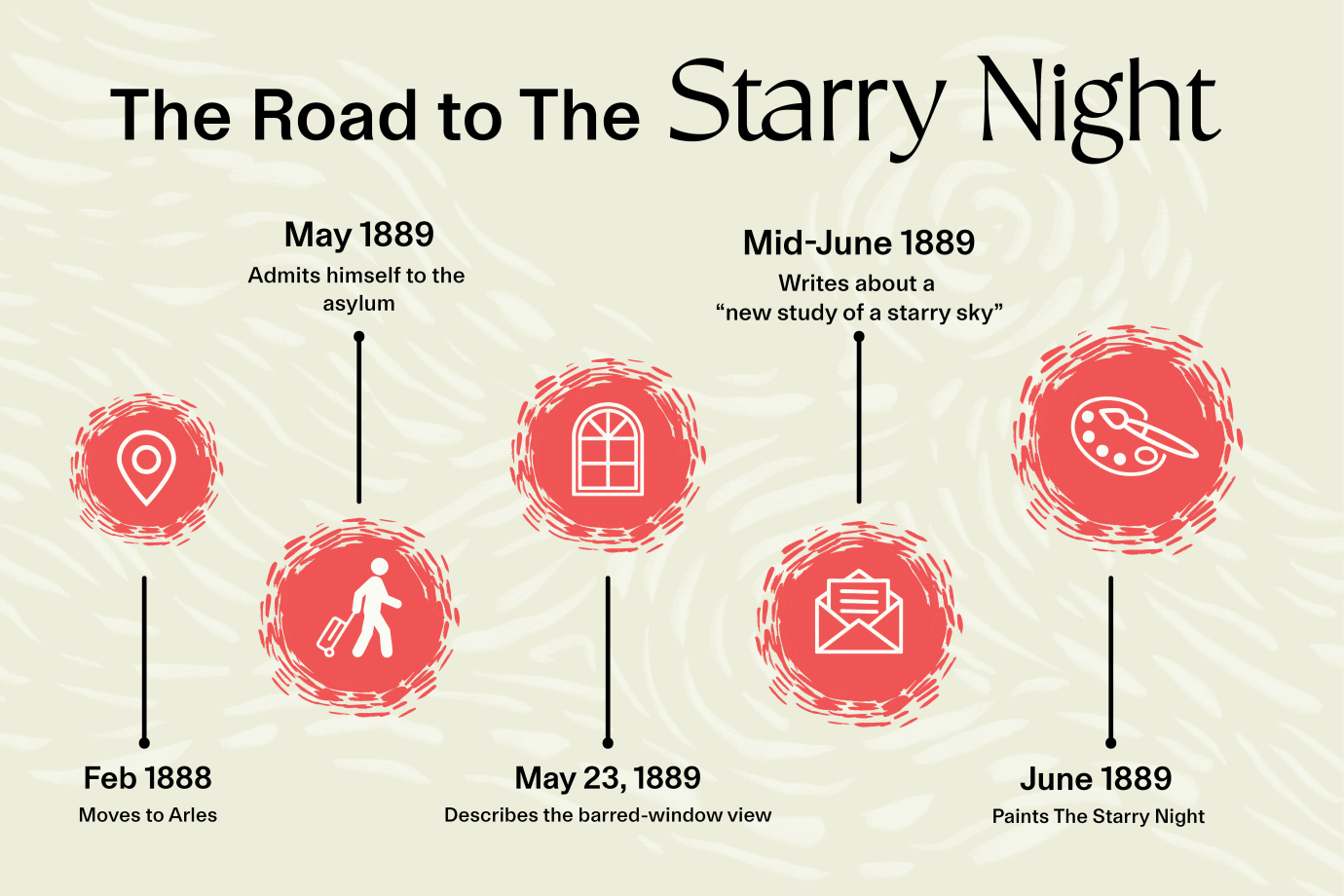

When van Gogh Painted The Starry Night: A Quick Timeline

Before we dive into the details of The Starry Night, it helps to map the key moments that led to it. With so many common misconceptions about why van Gogh painted The Starry Night in an asylum, we’re going to stick to what we know: the facts. Van Gogh didn’t paint this famous night sky in a random burst of inspiration; he painted it during a documented stretch of isolation, routine, and relentless artistic output. Here’s the rundown:

- Moving to Arles (1888): a fresh start in the south

In 1888, van Gogh moved to Arles in southern France, drawn to the region’s bright light and landscape. This period helped fuel his mindset for bold colors and expressive energy, later seen in his Saint-Rémy paintings.

- Admitting himself to the asylum (May 1889): structure and survival

After a mental health crisis, van Gogh voluntarily entered the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. The setting was restrictive, but it also gave him structure and a controlled environment where he could keep working.

- The barred window view (May 23, 1889): the real world behind the painting

In a letter to his brother Theo, van Gogh described the view from his room “through the iron-barred window”. The detail is important because it shows what his daily reality looked like and how closely he kept observing the landscape even while confined.

- The “starry sky” receipt (mid-June 1889): proof he was working on it

A few weeks later, he wrote to Theo that he had made “a new study of a starry sky,” placing the painting directly within his Saint-Rémy output. This line is one of the clearest primary-source clues connecting the moment to the work itself.

- Painting The Starry Night (June 1889): a masterpiece made in isolation

Painted at Saint-Rémy in June 1889, The Starry Night is an oil on canvas and is now held by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, one of the most famous works Van Gogh ever created.

With this timeline in place, the story becomes clearer: The Starry Night wasn’t painted from a single moment, it was shaped by a real sequence of events, observed surroundings, and van Gogh’s determination to keep creating.

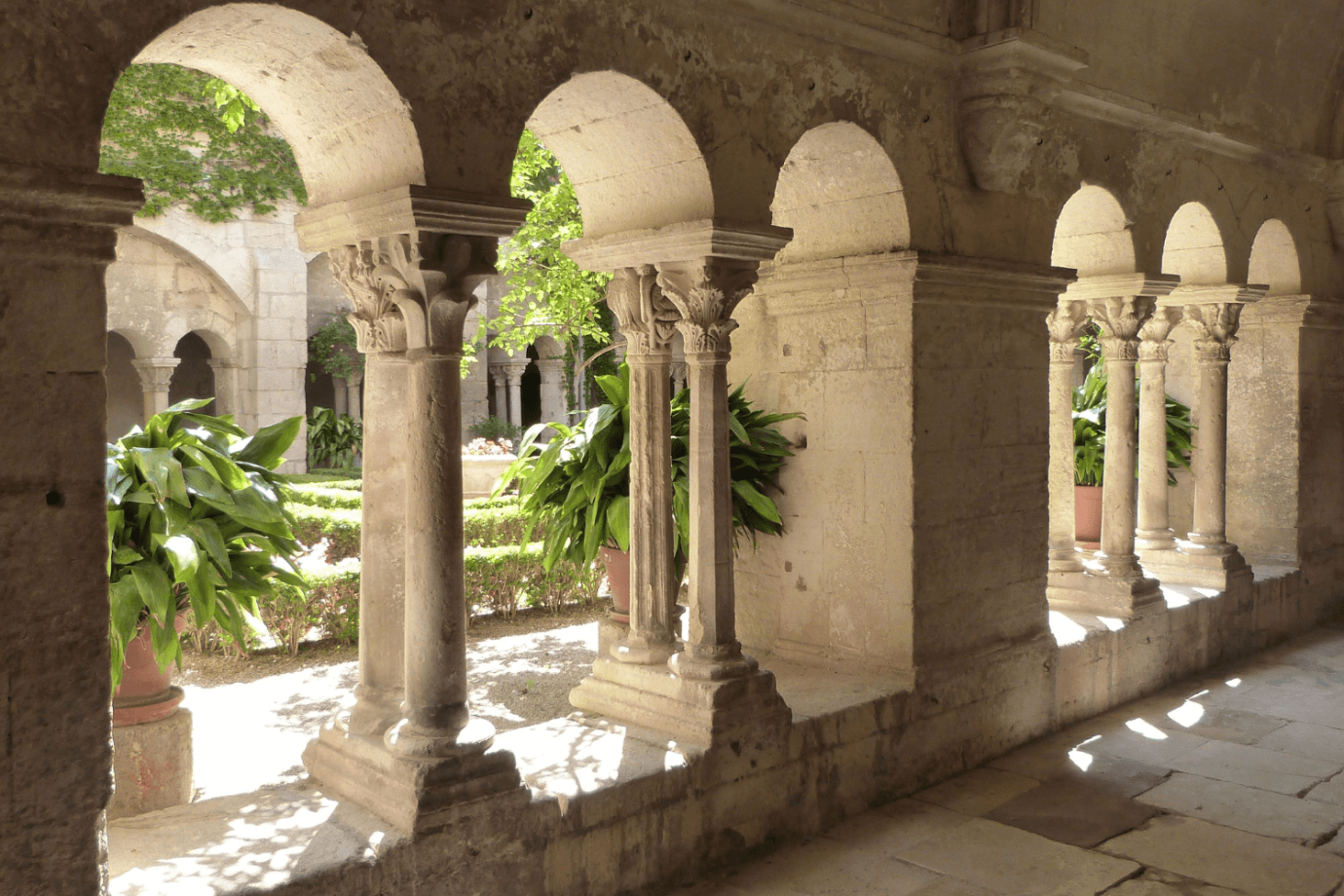

Van Gogh’s Experience at the Asylum in Saint-Rémy

In May 1889, van Gogh voluntarily admitted himself to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole psychiatric hospital in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, hoping for stability after a period of crisis in Arles.

The asylum was restrictive; patients lived under supervision and routine. But, it also gave van Gogh something he desperately needed: a contained environment where he could continue working. Art historian Richard Thomson (via MoMA) describes this period as one of isolation and complexity, with van Gogh cut off from family, friends, and fellow artists while trying to steady himself psychologically.

And van Gogh wasn’t vague about what life there looked like. In a letter to his brother Theo written shortly after his arrival, he describes his daily view “through the iron-barred window,” like a framed scene. This is one of the most concrete details we have about what he could physically observe from inside the institution.

“Through the iron-barred window I can make out a square of wheat in an enclosure, a perspective in the manner of Van Goyen, above which in the morning I see the sun rise in its glory.”

Letter to Theo van Gogh. Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, on or about Thursday, 23 May 1889.

That line is one reason the asylum story matters so much: it shows both confinement and clarity. He was restricted, yes, but he was still paying close attention to the world outside, turning what he could see into subjects and studies.

In the same letter, he mentioned that due to the amount of empty rooms in the building, he had another room where he could work. This goes to show that he never abandoned his creative mindset in the asylum, but rather, it became part of how he endured his time there.

Misconceptions About Why Van Gogh Painted The Starry Night in an Asylum

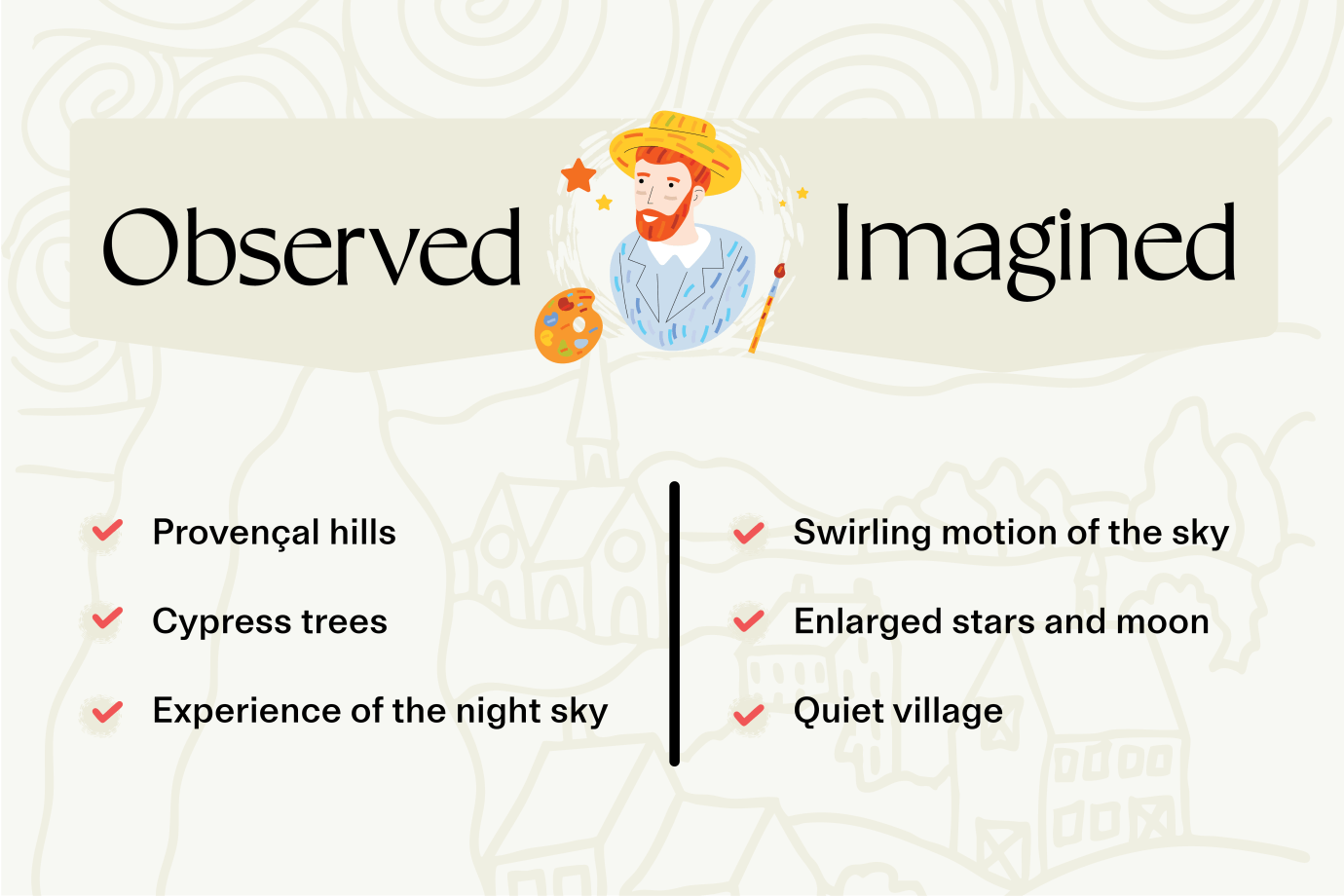

You’ll often find controversial takes about why van Gogh painted The Starry Night in an asylum, where people claim van Gogh was in a state of psychosis and painted the chaotic sky exactly as he saw it in real life. But the historical record points to something far more interesting and far more intentional: this wasn’t a literal snapshot. It was a composed scene, shaped by careful choices rather than a single moment of madness.

Inspired by real elements of the landscape around Saint-Rémy, van Gogh transformed what he observed into something expressive, building the final image through memory, emotion, and artistic invention.

What van Gogh Really Saw From His Asylum Window

As mentioned, van Gogh laid out a clear depiction of what he actually saw out his window in his letter to Theo. The square of wheat contrasting with the iron-barred window tells us he was clearly seeing an everyday view through a layer of confinement.

That letter matters because it anchors his surroundings in something concrete: real land, real light, and real observation. He wasn’t painting from pure fantasy, he was paying attention to the world he could still reach visually, even when he couldn’t physically leave it. Paired with his actual views, he used his artistic mind to imagine up the whimsical parts of the painting.

So, The Starry Night goes beyond observation. The Museum of Modern Art notes that key parts of the scene, especially the quiet village beneath the hills, were not visible from van Gogh’s window and were instead based on other views. In other words, the painting blends the environment of Saint-Rémy with a deliberately constructed “memory landscape.”

Why The Starry Night Feels So Powerful

The Starry Night doesn’t deliver just one simple emotion, it reveals a divergence of feelings. It can feel calming and intense, comforting and unsettled, like the night sky is both shelter and storm. That emotional depth isn’t accidental. It’s built through specific choices van Gogh makes across the composition.

Swirling Sky

The upper half of the painting is where the emotion hits first. Instead of a still atmosphere, van Gogh creates a sky that moves, built from flowing contours that sweep across the canvas. Richard Thomson’s analysis (via MoMA) emphasizes how these swirling forms read as coherent and intentional, turning the sky into something expressive rather than random.

Star Halos

The stars aren’t painted as distant pinpoints, they radiate outward in glowing rings. Those halos intensify the scene, making the night feel electric, almost vibrating. MoMA describes the sky as the most dynamic part of the work, and the stars’ exaggerated glow is a big reason the painting feels so alive.

Cypress Anchor

In the foreground, the dark cypress rises as a counterweight to all that movement. It stabilizes the painting with a strong vertical form like a visual anchor between earth and sky. Thomson notes that the cypress takes on an urgent identity here, reinforcing that it’s more than scenery: it’s a structural force holding the composition together.

Hushed Village

Beneath the sky, the village feels quiet and orderly. MoMA describes it as “hushed,” and that calmness is crucial because it gives the viewer a place to rest. The more still the town appears, the more powerful the swirling sky becomes by contrast.

Brushwork Rhythm

Part of the emotion comes from how the painting moves across its surface. Van Gogh’s brushstrokes create rhythm with short, directional marks that guide your eye like a current. It’s one reason the image can feel almost musical: you don’t just look at it, you follow it.

Crescent Moon

Finally, the moon acts like a visual “steady point” in a moving sky. Its bright, simplified shape gives the composition a focal light source; something stable enough to hold the viewer inside an otherwise turbulent atmosphere. It’s a small detail, but it helps explain why the painting can feel both intense and strangely comforting at the same time.

And when you remember where van Gogh painted it, from a place of confinement, the mood becomes even more striking: an expansive night sky created within a restricted world.

Why The Starry Night Goes Beyond Impressionism

It’s easy to assume the asylum is the entire explanation for The Starry Night, but the truth is more nuanced. The asylum didn’t “cause” the painting, it shaped the conditions around it. MoMA’s scholarly analysis frames this period as one of isolation and psychological complexity, even as van Gogh remained determined to keep working and evolving his art.

That drive comes through in his letters from Saint-Rémy: van Gogh’s voice is observant, reflective, and still committed to making art despite confinement.

And the result goes beyond Impressionism. Impressionist painters captured light and atmosphere, but van Gogh pushed those ideas further using bolder color, thicker brushwork, and dramatic movement to paint emotion as much as observation.

The Starry Night isn’t just what the eye sees, it’s what the moment feels like, and that emotional intensity is exactly what defines Post-Impressionism.

Keep Exploring: Bring the Night Sky Home

- Shop The Starry Night – Bring home the most iconic night sky in art history.

- Explore More van Gogh Prints – Discover more of his landscapes, florals, and color studies.

- See The Starry Night Reimagined – Modern takes inspired by The Starry Night from iCanvas artists.

FAQ: van Gogh & The Starry Night

▼View the Questions

Did van Gogh paint The Starry Night in an asylum?

Yes. He painted The Starry Night in June 1889 while living at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France.

Why did van Gogh enter the asylum in Saint-Rémy?

He voluntarily admitted himself after a serious mental health crisis, seeking stability and care while continuing to work.

Did van Gogh paint The Starry Night from his window?

Not exactly. The painting is inspired by his surroundings, but it’s not a literal snapshot; some elements were artistically constructed.

What did van Gogh actually see from the asylum?

In his letters, van Gogh describes looking out through an iron-barred window at the landscape outside, including fields and the surrounding countryside.

Was van Gogh “crazy”?

Van Gogh experienced serious mental health struggles, but reducing him to “crazy” oversimplifies a complex reality. Experts have suggested multiple possible diagnoses over time.

Where is The Starry Night today?

It’s in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City.

One comment